MEMORANDUM FOR: XXXXXXX

SUBJECT: Geographic Intelligence Memorandum on "Malaysia" -- CIA/RR GM 62-2

REFERENCE: xxxxxxx dated 25 April 1962, same subject

1. Your comments on subject report, which was produced on short notice at ONE's request, have been noted. The following paragraphs refer to the several points of content questioned.

2. UK rights in Singapore. We agree that the GM 62-2 statement, "... the United Kingdom... will retain the right to use the Singapore military base." should be regarded as subject to Federation leaders' permissiveness and local popular attitudes. These limitations, however, apply to the British situation presently -- the British could not, for instance, use Singapore against the Indonesians in New Guinea. Similarly, we felt that the residual sovereignty possessed by the host country is a limitation on freedom of action that is generally appreciated. The report announced by Prime Minister Rahman xxxxxxx

3. Malaysia Solidarity Consultative Committee. We agree that this committee does not represent all popular opinion. The term, "representative" was used in the sense that the committee is constituted of representatives from all of the political components interested in Malaysia xxxxxx. The fact of its "stacked" possibilities might have been made more explicit, although you will note that the preceding sentence intentionally refers to formation of the Cobbold Commission as a probable pro forma act on the part of the British Government.

4. The economy. It is certainly true that in an auto drive through Malaya one is impressed with the"hustle and bustle"; the economy has markedly improved since the period of the Emergency. On the other hand, based on the present knowledge of Malaya's natural resources, we believe it is unwarranted to claim, as you suggest "many expert observers" do, that the Federation has "very considerable economic potentials for the future." Our detailed conclusions on the Federation's resource base are available on request.

5. Map A. This map shows great-circle distances, not those of scheduled air carrier routes. "Airline" distances is the legend thus should have been "air" distances. With regard to the questioned citation of direct flights from Singapore to Manila, the Official Airline Guide for April 1962 lists four direct flights weekly by BOAC between Singapore and Manila. In addition, there were three flights weekly by Cathay Pacific Airways from Singapore to Manila via Hong Kong. We were wrong in showing direct flights to Sydney.

6. Map B. The omission from this map of the main north-south road in Malaya has its roots in an old cartographic problem -- how to show background detail without obscuring the main subcject on the map. In this case, there were a number of design complications which counseled omission of this road, as indeed many others. Concerning the main East-West route you are right -- portrayal of a major section of the road was based on an obsolete source. Concerning the road as entering Thailand, our information has it trafficable, constructed of crushed stone or blacktop of the motorable route on the east coast, we may both be in error -- a recheck here shows good evidence for the trafficability of all sections except that between Pontian and Rompin; this possible gap is to be closed by a new road to be completed in 1963.

7. Place names. Names on Map D were holdovers from a conveniently available base map which carried names only for rough orientation, and, in the process, gave preference to those of towns on railroads. The name and the presence of Map B as the primary map of Malaysa, no recompilation of this aspect of Map D was deemed necessary.

1. I read the subject memorandum with such interest. I found, however, that it contains several misleading statements in the text and quite a number of inexplicable omissions and commissions on the maps, particularly with regard to map B.

2. The statement in the second paragraph of the Introduction states "the United Kingdom ----- will retain the right to use the Singapore military base." This seems at least an oversimplification of a critical question. The Federation has agreed that the base can be used in the future for Commonwealth defense and to oppose Communist aggression in Southeast Asia. This does not mean, however, that the British would have full freedom of use of the base as the statement implies. It is certain that Federation leaders would make any final decision as to how and when the bases may be used and their permission will not necessarily be easily obtained. Local popular attitudes in Singapore itself will also limit use; the British say they cannot run the base in the face of local opposition. Striken alone could prevent its effective operation.

3. The Malaysia Solidarity Consultative Committee, also mentioned in the Introduction, is not a "representative body" at all. It is in face a carefully selected, stacked group which was intended to put the stamp of approval on Greater Malaysia for its sponsors -- Singapore Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew and Malayan Prime Minister Abdul Rahman. It is a propaganda vehicle which has only set three or four times and is not working out details / of merger. This is being done by the British and Lee and Rahman,

4. The discussions under Terrain and Economic Aspects convey what seems to me a not very balanced impression of the economy. Many expert observers think that the present Federation is the richest country in the entire East (except Japan) and that both the Federation and the Borneo territories have very considerable economic potentials for the future. Your study emphasizes economic problem (which all countries face) and does not appear proper relative weight to the many economic assets. Driving through all the Federations states, as I have done, impresses with its hustle and bustle, aggressive efforts at development and the general well-being of the people as compared with most other oriental countries.

5. A criticism of Map A is the omission of the airline distance to Bangkok, which is the major northern route from Singapore. If the red lines depicted on the map were intended to show air distances they would be accurate but the legend states they represent airline distances and therefore two are misleading. There are no direct flights to Manila or Sydney by scheduled airlines. Flights to Manila by PANAM (the only carrier) go via Saigon and those to Sydney via Darwin.

6. May B mystifies me. It has totally omitted the main trunk road from Singapore north through Kuala Lumpur and Ipoh to Penang as well as the major section of the main East-West route from Kuala Lumpur to Kuantan. The route shown on the map as connecting with Thailand is probably mostly a track; the motorable and primary route to Thailand from Penang through Alor Star is not shown. Incidentally, on the east coast, there is no motorable route (only overgrown track) between Endau (about 25 miles above Mersing) and Pekan. Many good shorter roads have been omitted and thus Map B fails to reflect the extensive and excellent road system of Malaya.

7. May C has very few place names on the map of Malaya but while omitting major towns like Georgetown, Kota Bahru, Kuala Trengganu, Kuantan and Kuala Lipis, it shows tiny villages like Jerantut, Tumpat, Kampong Nenasi (a fishing village not even connected by road) and Bukit Abu (which does not appear on either of my two detailed maps of Malaya). It is puzzling how the names of the latter group were selected as they have no particular significance.

8. I wonder why a draft of this study was not sent to this office for checking and correction. I think such a procedure would have made it look more professional.

Introduction

MALAYSIA

The concept of a political entity of Malaysia, proposed in May 1961 by the Malayan prime minister, Tunku Abdul Rahman, is based on the earlier "Grand Design" advanced by Malcolm MacDonald in 1950 as a long-range objective for British policy. Both concepts envision a federation that would include the 11 states of the Federation of Malaya, the State of Singapore, the crown colonies of North Borneo and Sarawak, and the sultanate of Brunei, a British protectorate.* The Federation of Malaysia would have a land area of about 130,000 square miles and a population of almost 10 million.

Once publicized, the current Malaysia concept rapidly reached the point of negotiation between the governments concerned and the British. To Malaya the plan offers an acceptable method of consummating what it deems to be a necessary merger with Singapore. In the new Federation the overwhelmingly Chinese population of Singapore would be counterbalanced by the predominantly non-Chinese populations of Malaya and British Borneo, thus precluding Chinese domination. Lee Kuan Yew, prime minister of Singapore, also favors the proposed federation but stipulates that Singapore should retain the right to maintain its own policies in the fields of labor and education. Should Singapore acquire complete independence, instead of becoming a part of the new Federation, Lee fears that it would become a left-wing Chinese political entity surrounded by Malays -- "the Israel of Southeast Asia." Britain favors the proposed Federation, with some reservations, and will relinquish sovereignty over Singapore and British Borneo to Malaysia upon actual federation. Although none of the component states of Malaysia is a member of SEATO, the United Kingdom, which is a SEATO signatory, will retain the right to use the Singapore military base. Before the federation is consummated, however, and apparently chiefly as a pro forma act in keeping with the British policy of self-determination, a five-man Commission of Inquiry is first to ascertain the views of the people of Sarawak and North Borneo towards the new Federation and to confer with the Sultan of Brunei. Many in British Borneo have reservations about joining the Federation although guarantees of a privileged position have been offered by the Malaysia Solidarity Consultative Committee, a representative body that is attempting to work out details of federation. From the Communist element, which views the Malaysia concept with alarm, dissension and possibly violence can be expected.

Difficulties emanating from the underdeveloped economies as well as from the ethnic complexity of the components may affect the viability of the new Federation. Heavy dependence upon income from products of primary industry, particularly tin and rubber, will expose the economy of Malaysia to considerable instability resulting from international price fluctuations. Furthermore, none of the component states is self-sufficient in its main food staple, rice, and all must depend upon imports of up to 50 percent of their needs, as in the case of Sarawak.

Dynamics of Location

Of paramount consideration is the location of Malaysia, no part of which is more than about 7 degrees from the Equator (see Map 35842A). Most of the area has a tropical climate, with heavy rainfall and uniformly high temperatures. These characteristics have had a marked influence upon the development of the local economies, notably in the fields of agriculture, lumbering, and trans- portation.

The specific locations of the component states have further significance. Singapore owes its importance chiefly to its position at the entrance to an interocean bottleneck, the Strait of Malacca, which has been likened to the man-made Suez and Panama Canals. Singapore thus controls the main east-west connection between the Indian and Pacific Oceans (via the South China Sea), and along the north-south axis, it occupies a strategic position between mainland Asia and Australasia. As a consequence, international shipping transiting the area generally stops twice at Singapore -- once on the outgoing trip and once on the return trip thus doubling much of the port's trade. Should the much-discussed Kra Isthmus canal across peninsular Thailand from Victoria Point to Chumphon (see Map 35842A) be constructed, however, the strategic importance of Singapore's position might well decline, since the proposed canal would shorten the distance and sailing time between ports of East Asia and the Indian Ocean.

-------------------------

*

In this memorandum, the term "Malaysia" applies to the proposed Federation of Malaysia, "Malaya" to the present Federation of Malaya, and "Singapore" to the State of Singapore. "British Borneo" refers to the combination of North Borneo, Brunei, and Sarawak.

As evidenced by these statistics, the percentage decrease of Chinese in Ma-laya and Singapore has been offset by the increase of Chinese in British Borneo, and consequently Chinese will still represent about 42 percent of the total population of Malaysia. Undoubtedly, they offer a challenge to the new Federation because of their greater cohesiveness, dominating position in business, and relatively high standards of education. In Sarawak, in 1960, less than 35 per-cent of the school-age population of Malay, Dayak, and other native groups was in school, in contrast to 80 percent of the Chinese children, most of whom attended the 231 primary schools that are under Chinese management and in which Chinese is the medium of instruction.

In British Borneo a distrust of Malaya and racial pride are among the parochialisms that will have to be faced by the new Federation. Many in British Borneo fear that the area will be colonized by the more advanced peoples of Malaya, and indigenous peoples such as the Sea and Land Dayaks of Sarawak refuse, as a matter of racial pride, to use Malay in their schools although Malay and English are the official languages. Consequently, as its Education Department indicated in 1960, Sarawak lacks even the unifying force of a lingua franca.

In contrast to such possible divisive forces is the potentially significant unifying influence of the Islamic religion, which is professed by an estimated one-third of the population of British Borneo and by an overwhelming majority of the Malays of Malaya. The terms "Malay" and "Muslim" have become almost interchangeable, and nominally any convert to Islam in the Malaysian area is known as a "Malay."

Present economic dependence upon such products as rubber, tin, and petroleum holds hazards for Malaysia beyond those inherent in the erratic prices on the world market. The natural-rubber market is threatened by competition from the synthetic product. In an effort to insure competitive pricing of natural rubber, high-yielding trees that produce 3 or 4 times present yields have been planted. For tin and petroleum, the future is more uncertain. Although the Kinta Valley of Malaya, near Ipoh, is still the world's most productive tin field, deposits of high quality Malayan ore are being depleted. Since no important new tin resources have been found, a reworking of already mined grounds may become necessary for continued production, thus increasing the cost of Malayan tin and making it less competitive on the international market. Similarly, production of crude petroleum from the Seria field in Brunei, the chief source of oil in British Borneo, is declining. Output as of mid-1961 was down to 83,000 barrels daily as compared to a peak of 120,000 barrels in mid-1957. Extensive exploration, offshore as well as on land, has failed to locate any important new deposits.

All of the components of Malaysia have adopted plans for improving their economies. In Malaya 3.5 million acres are currently in rubber; of these 2 million are in estates and 1.5 million are in holdings of less than 100 acres, with the majority less than 10 acres. Although this is a relatively equitable distribution, Malaya is making a significant effort to broaden the land-ownership base. The economic plans of Malays and British Borneo involve the opening up of new agricultural lands to provide holdings of economic size to more of their people.

Possibly even more important from the point of view of the Malaysian economies is the need for diversification, with emphasis on industrialization. Brunei, with its overwhelming dependence on oil, is particularly in need of diversification. Industrialization is of major importance for Malaya, because of the increase in its urban population since 1951, and for Singapore, because of its limited land area, decreasing entrepôt trade, and growing unemployment. The Pioneer Industry program of Malaya, with its tax-free benefits to approved new industries, and the work of the Economic Development Board of Singapore provide further evidence of the efforts being made by the component parts of Malaysia to develop viable economies that will be essential to the survival of the new Federation.

The total population increase from 1947 to 1960 was 74.1 percent. Although the Chinese population increased 68.6 percent and the Malay 99.7 percent during this period, the percentage of Chinese to the total population declined only slightly -- to 75.3 percent. The birth rates of all segments of the population are high and, as a result, about half of the population of Singapore is under 19 years of age. The overall density amounts to almost 8,000 persons per square mile on the 210-square-mile island. Actually, however, 75 percent of the population is concentrated within the limits of the city, which occupies some 32 square miles on the south side of the island.

British Borneo (Sarawak, Brunei, and North Borneo): An outstanding characteristic of the population of British Borneo is its great diversity. In the complicated ethnic picture are many tribal groups that differ from each other in language, customs, and economic pursuits. In Sarawak, for example, the census category, "Malays and Other Indigenous," includes Malays, Sea Dayaks, Land Dayaks, Melanau, Kayans, Kenyahs, Bisayaks, Kedayans, Kelabits, Muruts, and other smaller groups. Even within groups such as the Sea Dayaks, the language of a tribe in one area may be unintelligible to a tribe in another area. For most of the indigenous people, group consciousness does not go beyond the confines of the village. The ethnic composition of the population of British Borneo by number and percent is presented in the following tabulation:

The increase in the percent of Chinese is particularly significant in view of the great diversity among the other groups. Unlike Singapore, North Borneo has a perennial shortage of labor which is met through the immigration of migrant workers. Some 10,000 Indonesian migrant laborers may be found in the Tawau-Sandakan area at any given time.

Tasks and Challenges

Major sources of possible friction in the Federation of Malaysia will be its ethnic complexity and the inherent fears and antipathies among its peoples. Malaya, which has dreaded being swamped by the predominantly Chinese population of Singapore, sees a possible solution to this problem in the combined population of the new Federation. A comparison of the number of Chinese in each component and in the total population of Malaysia is shown below for 1960 and 1947:

The position of British Borneo on the island of Borneo is noteworthy in the context of potential ambitions of a nationalistic Indonesia, which currently governs three-quarters of the island. The 900-mile international border on Borneo extends through a sparsely populated, generally densely forested, mountainous region; only a very small segment of the boundary in the area southwest of Kuching has been demarcated. When the primitive people of interior Borneo move across this border, they almost certainly do so in total ignorance of the existence of a boundary. The location of the Indonesian-owned Natuna Islands midway between British Borneo and Malaya may create further difficulties should Indonesian expansionist aspirations toward British Borneo materialize. Some reports also indicate that the Philippines may press an old claim to North Borneo that is based on a grant given to the Sultan of Sulu in 1704. Groups in North Borneo opposed to federation would probably seize upon any of these situations to further their attempt to block the formation of Malaysia.

The proximity of Malaya to Sumatra, in conjunction with the ethnic and religious affinities of their peoples most of whom are Malay stock and adherents of the Islamic religion suggests possible future relations between Malaysia and Sumatra. Malaysia would probably offer attractions for the Sumatrans, who are traditionally more conservative than the Javanese, should the Indonesian Government move too far to the left politically. During the Japanese occupation, Sumatra was governed from Singapore.

Terrain

The terrain of much of Malaysia is not conducive to human occupance and economic development. The interiors of Malaya and British Borneo are mostly mountainous and densely forested; and the extensive coastal swamps, especially in Sarawak, not only are unsuited to settlement but also impede access to the interior. Largely as a consequence of the restricting influence of the forests, the swamps, and the infertile lateritic soils, an estimated 80 percent of Malaysia is uninhabited and devoid of any form of productive economy. Population concentrations and economic activity are chiefly in the foothills, along some of the valleys, and on the coastal plains. Transportation routes are restricted. and inadequate. Where they exist, the routes not only serve as unifying elements among the settlements but also set the pattern for future development, as in the case of the Malayan rubber plantations, which generally became established in areas that could be serviced by the existing tin-field rail lines.

Economic Aspects

The economies of the components of Malaysia are dominated by agriculture except for Singapore, which is dependent upon trade, and Brunei, which relies on petroleum production. Non-food commodities -- principally rubber, palm oil, and copra or coconut oil -- are the chief agricultural products of Malaya on

the basis of both acreage and value. In British Borneo the same crops rank first in value but they are surpassed in acreage by food crops, chiefly rice. The major nonagricultural products are tin, petroleum, timber, iron ore, and bauxite (see Maps 35842B and 358420).

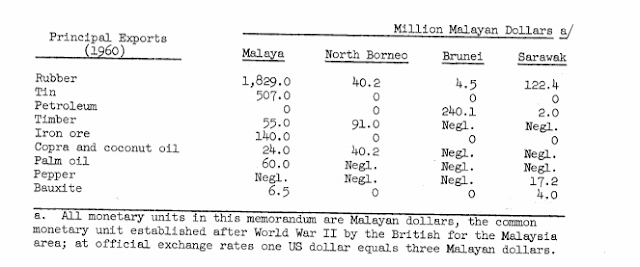

An indication of the relative importance of these products in the economies of the producing components of Malaysia is given below:

Malaya obviously will be the main source of exports from the new Federation, and the chief exports, at least for the near future, will be rubber, tin, petroleum, timber, and iron ore. Currently, the economies of the Malaysian components are not complementary, although much of the petroleum produced in Brunei and in the Miri field of Sarawak is processed and refined in the Lutong refinery of Sarawak (see Map 35842c). Malaya and Singapore, however, are pushing industrial development, and new industries may use some of the primary production as raw materials. Federation probably will benefit Singapore (which in recent years has been plagued by decreasing trade) because the components can be expected to channel more of their trade through the port.

In addition to being a focus of interocean shipping, Singapore is a main port of exit and entry for much of Malaya and a center for the coastal trade of Indonesia and British Borneo. Raw produce from these areas is sent to Singapore and, after processing, grading, and packing, is exported to world markets.

In 1959, the total trade of Singapore amounted to $5,826.2 million, of which $3,105.6 million were imports and $2,720.7 million exports, leaving an unfavorable trade balance of $384.8 million. The main imports were rubber, petroleum products, rice and other foodstuffs, and textiles; the chief exports were rubber, petroleum products, ship and aircraft stores, and rice and other foodstuffs. By value the chief sources of imports were Indonesia, the United Kingdom, Japan, and Sarawak; and the chief recipients of exports were the United States, the United Kingdom, "Other Countries in Europe," Japan, and Indonesia. In 1959, Indonesia provided 37 percent of the imports by value but received only 4.8 percent of the exports as compared with 14.2 percent in 1958 - a decrease caused largely by a virtual embargo on textile imports by Indonesia. In view of the economic difficulties of Singapore, it is worth noting that British military bases there employ directly 35,000 Singapore citizens and indirectly, many thousands more.

Demography

Malaya: The estimated population of Malaya in 1960 was 6.82 million or about The following tabulation 70 percent of the total for the entire Malaysian area. gives the 1957 census figures for the ethnic composition of the population by number and by percent of the total and, for purposes of comparison, the corresponding percentages for 1947.

Significantly, the 1957 census shows that, of the 2.67 million persons in urban centers, 64 percent or 1.7 million were Chinese. (The percentage of Chinese to the total population by second-order administrative division for the Malaysian area is shown on Map 35842D.)

Because of restrictions on immigration of other races since 1931 and a higher birthrate among the Malays, the percentage of Malays to the total population increased slightly between 1947 and 1957, whereas the percentage of Chinese decreased slightly. Projections indicate that the proportion of Malays can be expected to increase to 51.6 percent by 1972 and that of Chinese to decrease correspondingly. The segment of population involved will still be under voting and employment age in 1972. At present about 60 percent of the population is under 21 years of age.

The Malay population has its chief concentrations in the rice areas of the northeast and northwest and along the Johore coast, whereas the Chinese and Indians are most densely settled in a belt about 40 miles wide along the west coast. The concentration in this belt, which coincides largely with the areas of tin and rubber production, reflects the importation of Chinese and Indian laborers by the thousands during the 1800's.

Singapore: The official estimate of the population of Singapore as of June 1960 was 1,634,100 or about 17 percent of the total population of the Malaysian area as of 1960. Its ethnic composition by number and percent follows:

end.

Comments